JOSEPH AND JEAN MEAUCHAND; THE FORGOTTEN ONES

I don't know why, but the closer you get to the historical period where the transition from the baroque bow to the modern bow took place, the more dense the fog becomes, almost swallowing craftsmen such as Meauchand. Why is this? On the one hand, it is difficult to find historic documentation; on the other, I have the impression that whoever wrote down history didn't like what he found.

Cramer model, Jean-Jacques Meauchand

After the Tourtes, the Meauchands were the second family who dedicate themselves completely to bow making.

The father, Joseph, of whom we know very little, is set to have been born in 1720. On the 8th of January 1754, he married Anne Philiberte. He started up as a violin maker, became interested in bows and went on to become one of the first bow makers dedicated entirely to this profession. When the wife died, on the 10th of November 1771, the inventory of his estate indicates a state of poverty.

It seems that in his youth, he made bows with convex curves and “Pike heads”; though no examples have been found.

After 1770, he also took up the famous “Cramer” model, and he began to mark his bows. Even though he never left Mirecourt, his mark shows the words “MEAUCHAND in PARIS”. In those years Mirecourt, did not belong to France, but to the dukedom of Lorena, and he used this small trick to evade the border taxes.

He died on the 31st of January 1775.

The son of Joseph, Jean-Jacque, was born on the 25th of July 1758. He became a bow maker as well, and he was tough the profession by his father. Jean-Jacque married Elisabeth Chopin, related to the famous pianist, on the 5th of October 1784, and he died on the 8th of March 1817 in Mirecourt.

We have now covered the personal data, and can concentrate on their work, because it is very likely that the first French “Cramer” models were not made by the Tourte.

In the biographical part of “L'Archet” dedicated to Jean-Jacque, you can read as follows: “He began his apprenticeship in 1770, making Cramer models. There was a large demand from Germany, thanks to the violin maker Francois Lupot I (not to be confused with Francois Lupot II, his son), who had moved to Stuttgart in 1760, and bought the bows to his German clients from Mirecourt.

So far so good - except that the “Dictionnaire Universel des Luthiers” by René Vannes says that Francois Lupot I arrived to Stuttgart in 1758 and stayed there until 1766 where he returned to France. He was in Orléans in 1769, and in Paris in 1794. Thus, he was not in Stuttgart in 1770.

There are two questions: did the old Lupot continue to trade with Germany after he returned to France (quite unlikely because in 1766, his patron The Duke of Württemberg passed away which was probably the reason for Lupot's return to France)? Or the first French Cramer models (high head, convex curve and possibly in pernambuco - technically modern bows), were neither made in France, nor by the Tourtes.

If you remember the former post, “L'Archet”, speaks about a visit in Paris by the great violinist Wilhelm Cramer in 1769, during which the oldest of the Tourtes, Nicolas Leonard, had the opportunity to experience the new bow model; the Cramer model.

Apart from the fact that the dates do not match the dates in the L'Archet, there would also be an intuitive side of the matter of how things went.

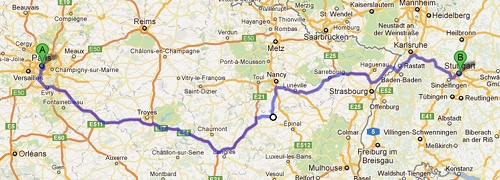

The Tourtes had not jet obtained fame in 1760. So, would someone in Stuttgart in need of a bow travel all the way to Paris by means of transport that were far more uncomfortable than today and pay the border taxes; or would they perhaps stop in Mirecourt, a town which was a part of the dukedom of Lorena until 1766, and which, at that time, was already very active in the violin making industry?

The white spot is Mirecourt

The Tourtes contributed greatly to the initially mechanism of the frog and to the style of the bow. Never the less the conclusion is that the spring was already there. Since the bow basically works as a leaf spring, the modern curves made in the beginning of the period were not French.

So long,

Paolo

|