EUGENE SARTORY; CELLO 1930

Some weeks ago I had the fortune to keep a beautiful Eugène Sartory violoncello bow for some days, which I will analyse in just a moment. First off all I want to thank CR. Forma – The special education services in the Province of Cremona, who gave a very interesting conference last week, dedicated to the French School of Bow making held by M° Jean Francois Raffin.

Violoncello bow by Eugène Sartory 1930 There is really nothing to say, and there is no doubt; when you find yourself with a Sartory in your hands you understand immediately why it had so much success. The history of bow making is full of craftsmen with great working skills; the most striking one would be J.J. Martin, who had a talent so great it allowed him to make bows with a perfect cut even if he had only one eye. To understand the difficulty you could try to drive a car with one eye closed; an experience worth a thousand words.

From a mechanical point of view the good Martin was superior to Sartory, surely because of his talent but also thanks to his teachers. Martin had studied with Maline to begin with, then with Maire during his Parigian period (1858/63), both students of Etienne Pajeot; the old school – the great school. When the jung Eugène began to make bows himself, unfortunately all the great craftsmen from the past had joined a higher social level, and he had to settle for Charles Peccatte as a teacher; not exactly the best. This is the reason to why Sartory was placed below his great predecessors. If he had only intuited that the curves he made had enormous limitations, and if he had then used antique mechanics, he would have outclassed many noted names.

The fact that Eugène Sartory had a defined opinion on the rest of the bow making craft gets very clear when analysing one of his bows. Sartory had another way to look at things compared to his contemporaries, which was not approved. First of all the choice of material. We must not forget that he started to work in the Bazin period; dense and dark material was used, though without excellent performances.

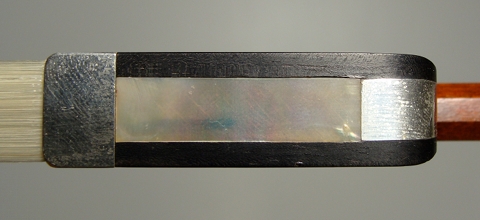

As you can see in the photo, Sartory, was of another idea. Not that bows of a dense and dark material made by him doesn't exist, but these two parameters weren’t the only ones he took into account. The capability to read and understand the wood was the fundamental difference that distinguished him from his contemporaneous colleagues. His choices follow mechanical/acoustic criteria very much like illustrious predecessors like Tourte and Persoit. Whether it is yellow, red or black doesn't count, as long as it can play.

As you can see in the photo, the bow is made in a light brown wood, which surely was even more bright when he made it. After eighty years the sound of this bow has a speed superior to 5500 m/s; a miracle to a bow from 1930.

I want to add a small parenthesis to speak about a mechanical improvement. Observing the photo above you notes the octagon which continues from out under the dressing; in this case in an extreme way, moreover, since it is a violoncello bow. The motive was mechanical, not aesthetic. The modern curves, other than being very rigid, tent to yield on the middle. Since the octagon shape is more rigid than the round shape, Sartory tried to add resistance leaving the octagon much longer. Pointless; the project was wrong.

I had had the possibility to see the bow before it was brought to be certificated by M° Raffin in Paris, and I had come to the exact same conclusion. The dating of this bow suggest another very important aspect of the work of Sartory; 1930.

Besides being an excellent craftsman, Eugène Sartory was also great trader. He even went to the United States of America to bring a lawsuit for infringement. Trading and making bows are two different things, and even if one is capable in each field, either one of them takes time. The history show us that more than one craftsman has put out his career, trying to do both. Yet again Martin is a good example. When he tried to expand the production of bows in the late 1860'ties, he failed to maintain the stability of the quality level of the product, and failed miserably in 1881.

This was not the case of Sartory; he was better. First of all, the idea of a small fabric was far from him. When the work began to increase he chose few but very good craftsmen, who could lent him a hand. Much more like Etienne Pajeot, who had Maire and Fonclause to work for him.

Sartory also had fortune with his staff. In the very beginning, before the First World War, he had the assistance from some young germans like Otto Hoyer (which is why he was called Le Parisier back home) and afterwards a very young Louis Joseph Morizot.

Sartory met his last collaborator, Louis Gillet in 1935, who stayed by his side until his deaf in 1946. Sartorys real luck occurred half way into his career, when he started to collaborate with the great and to often forgotten Jules Fetique.

A shy craftsman who was less gifted as a trader, and therefor less known, but with excellent manual skills and a stylistic taste not less than Sartory. Within this collaboration some of the best bows of the 19th century have been made. As well as being powerful, defined, with an enamelled and biting sound, they are aesthetically perfect and attractive, all marked with fire.

To read more about this topic: J.J. MARTIN; THE LAST GREAT ONE EUGENE SARTORY; BELGIAN MOUSTACHE HIDING A FRENCH SMILE NICOLAS MALINE; BOWMAKER AND ENTREPRENEUR NICOLAS MAIRE REMY; THE HUMBLE CHARLES NICOLAS BAZIN; THE FOUNDER FRANCOIS XAVIER TOURTE 1820-25 JEAN-FRANCOIS RAFFIN; THE CHOSEN ONE EUGENE NICOLAS SARTORY; THE VELOCIRAPTOR ETIENNE PAJEOT; THE THOUSAND-HEADED BOWMAKER LOUIS JOSEPH MORIZOT PERE AND THE DYNASTIES LOUIS HENRY GILLET; THE POOR MAN'S SARTORY JULES FETIQUE; THE OTHER SARTORY

Paolo

|

|