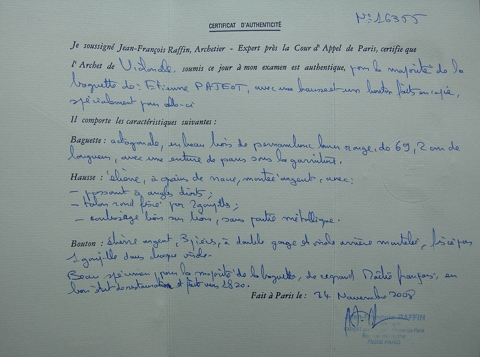

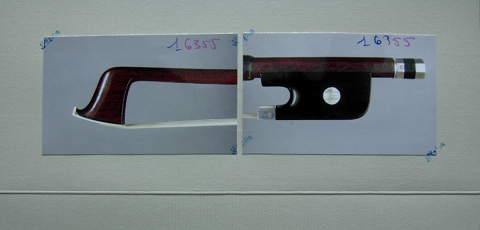

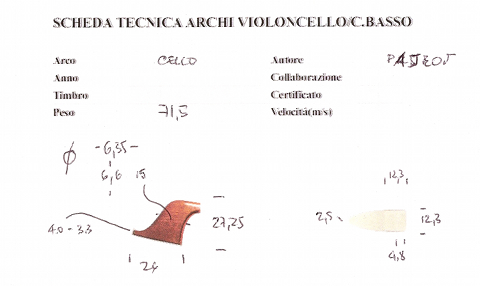

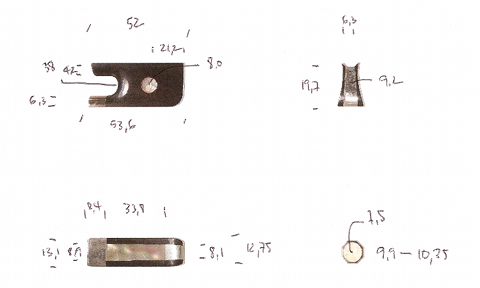

VIOLONCELLO BOW by ETIENNE PAJEOT 1820I know this piece, and you know it too, because you have met it several times in this blog. I just haven't stopped for long enough on one of the bows that shows not only the greatness of the author but also represent a truly Accademia Superiore of bow making. One of my most important masters; Mr. Pajeot. Cello bow by Etienne Pajeot 1820 ( Clic to enlarge ) As I may have told you, Etienne Pajeot, the author of the marvellous piece shown above, comes in third on my personal list of favourites, superseded by F.X. Tourte and J.P.M. Persoit in a joint first place. More important than the ranking itself, however, is the reason why this master is so prominent. The fundamental parameters for expressing objective judgement on the work of a bow maker are three: technical capacity, creativity and last but not least, the capability to understand and know how to form the wood. These make the difference between a great and a good craftsman. We will take for granted the enormous talent that Pajeot had with the utensils and just pass on to the creative aspect. As I have often discussed, the various styles had not yet been standardized in this period of French bow making. Having schools to teach this craft only started in the second half of the 1830's. The bow makers were almost completely free to act and propose their own preferred style, without a rigid overall structure being imposed upon them, as seen in the years to come. In those years it was not uncommon to see different developments of styles that seem quite unusual today. One knows that creativity is not every man’s gift and the schools did alter the average quality level of the bows. Obviously this did not count in the case of Pajeot. Not only did he suggest a violoncello bow with a head very similar to the head of a violin bow’s head; he also made it in a way that was incomprehensive and therefore impossible to copy by anyone else. There were other craftsmen at the time or just a little bit earlier on, as his father for example, who had made heads of a similar style, but no one with the same fluency. Photo 1 Photo 2 The composition of the head of this bow is absurd. The chamfer seems not to have any relation to the wedge, and furthermore, the bow is unusually long for a violoncello bow. Nevertheless, it all blends beautifully and results in a delightful sensation of lightness. Let us try to understand how he achieved this. The head of this bow is incomprehensible until looked at in a three-quarter angle as shown in the photos above. Observing the front, to begin with, you do not get the relation between the circumference of the throat, the circumference of the wedge as well as the one of the ivory tip; they appear completely incompatible. You then note that the inner circumference of the throth is much more narrow than the external one, which then seems quite similar to the one of the wedge, as to the circumference of the ivory tip although not completely identical. Let's return to the length. The head of the bow is short, but he has had to stay low on the wedge to obtain the slant of the profile. Though in this way, deprived in thickness, he has had to regain one tenth to assure the head and is therefore forced to make the internal circumference of the chamfer very small and go down straight instead of coming back in, as it is usually done on violoncello bows. In this way he has completely disconnected the harmonious lines of the head; the stroke of genius is how he has been able to regain this. You can see this in the photos below. Technically it enters very much on the cheeks, doing so creates a sliding illusion which serves to harmonise it all. That is why you will note, observing PHOTO 1, or 2, that it is much more similar to a violoncello bow than if viewed only from the front. Observing the three circumferences of the external chamfer, the wedge and the one of the ivory tip from the front, seem to be almost perfect, whereas observed from a three-quarter angle you will see that they relate just perfectly and it seems like the chamfer has been set into the wedge. A stroke of genius! At this point, if there is to be any doubt about the level of this man the definitive confirmation has to be his choice of material and his capability to shape it. This bow is one of the few miracles that I have had the fortune to see. The wood is still very strong and vibrates just as a tense string. However, the most surprising aspect is not the resistance that is still retains after about 200 years, but the proportion of weight/strength; this bow is light as a feather. In this case the immortality is credit to nature as well as to Pajeot. As you can see in the photo above, the stick has been cut perfectly and it is so slim that it seems like a viola bow. The wood is not particularly dense, but the speed of the sound is still extremely fast; above 5600 m/s, which leads me to believe that when he made it, this stick reached more than 6000 m/s. Now Pajeot. This is the best preserved curve on a violoncello bow that I have ever seen. Even though this piece has been used a lot, the curve is absolutely perfect. It is not only evenly distributed, but the amount of the curve is still intact. As you know, the superiority of the antique curves to the modern ones, apart from the sound, is the mechanical project behind. The curve has been studied in a way that when it loses some of its energy the bow will extend but keep on functioning due to accurate engineering. This bow is different, because it has still got as much curve as the day Pajeot finished it. I don't know if it is his merit or if nature lent him a hand. What makes me think that Pajeot was extraordinary in his work, is that I know by experience, that the more beautiful the material the more nuts it makes you when working it; in this case it must have been a hard struggle. Unfortunately the frog is not the original one. However, the copy has been done by an outstanding craftsman; M° Daguin. The choice of material is perfect, especially the ebony, and the style is very well accomplished. In fact I have had to study the button for a long time to establish that it is a copy. Not only have I introduced it to you, I can also offer it to you. The “criminal” owner of this bow (I so hope he will change his mind) has put it up for sale. As you know, I only trade in antique bows in exceptional cases - and this sure is. For a moment I was tempted to place an offer myself, but then I questioned my manic collector’s gene. Although I appreciate these pieces in a very profound way, they were not made for a museum, they were made for playing, and those still playing, like this one, are supposed to remain the property of musicians. I do not take part in the negotiations, but only present it to you here. If you are interested and would like to see, try and listen to this marvelous piece, do contact us to make an appointment and come and visit us. The negotiations are left private between seller and buyer, without any profit. ...and to you, ”criminal”, as I know you will be reading: do not sell! Certificate by Jean Francois Raffin Specifications and measurements If you want to deepen this topic: FRANCOIS XAVIER TOURTE 1820 -25 VIOLIN BOW by JEAN PIERRE MARIE PERSOIT 1820 C.CA So long Paolo

|

|